Climate Migration Explainer

SEPTEMBER 2023

This Explainer aims to promote a deeper understanding of key concepts, numbers, and terminology defining the interrelationship between the climate crisis and movement of people within and across borders—to inform greater understanding, and offer principles to guide solutions.

It is not meant to be a definitive guide to the ever-expanding body of data, research, or life experiences of people impacted by the climate crisis.

1. Understanding Climate Migration

3. The Numbers

For more information, contact info@climatemigrationcouncil.org.

About IOM, contact mecrhq@iom.int.

About Emerson Collective’s climate displacement work, contact shana@emersoncollective.com.

This Climate Migration Explainer was authored and edited by IOM and Emerson Collective, with review by the Climate Migration Council’s Academic Work Group.

1. Understanding

Climate Migration1

The worsening impacts of the climate emergency are affecting populations worldwide and increasingly shaping whether, where, and how people move (or do not move) depending on social, political, economic, and environmental contexts. Climate change compounds existing risks confronting communities across the globe, and affects various communities unevenly depending on their capacity to build resilience in the face of climate impacts.

As noted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, the impact of climate change on human mobility is multidirectional: “Specific climate events and conditions may cause migration to increase, decrease, or flow in new directions.”2 Climate hazards can displace people directly, through the impact of sudden-onset events such as hurricanes, floods, or fires. Climate hazards can also displace people indirectly, through slow- onset processes such as drought, erosion of coastlines, and increased heat, which can have negative effects on livelihoods, income, or food security and compel people to move.

Climate mobility implicates many fundamental human rights and therefore must be considered from a rights-based approach. When people desire to stay in their home communities, it is critical to support their right to do so by investing in resilience and preventing avoidable climate- related displacement whenever possible. It is equally essential to support freedom of movement by protecting people who have been displaced and designing safe mobility pathways for more proactive movement when people are impacted by either slow or sudden onset climate hazards.

It is within this context that we aim to create more equitable migration policies and solutions for all people on the move, as well as to build resilience among communities affected by worsening climate hazards. Migration may contribute to climate adaptation and disaster-risk reduction when well managed. With supportive policy and legal frameworks in place, climate- related movement can offer positive outcomes for migrants and host communities, despite its hazardous origins. With regard to existing migration frameworks, the IPCC has indicated that “the more agency migrants have (i.e., the degree of voluntarity and freedom of movement), the greater the potential benefits for sending and receiving areas.”3

Cities are crucial actors in the response to climate mobility. They already receive and will increasingly receive migrants moving from rural or coastal to urban areas. At the same time, cities are also exposed to climate hazards, such as flooding, sea level rise, or water scarcity. Subnational leaders thus play a key role in integrating internal and cross-border migrants, and in building resilience against worsening hazards.

1 The term migration as used in this explainer is conceived as an umbrella term referring expansively to human mobility, including the different manners in which people move in contexts of climate change. While no agreed definition exists at the international level (see definitions section below), human mobility in contexts of climate change occurs on a continuum, which includes immobility, forced movement, and more voluntary movement in which migrants possess various degrees of agency.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CLIMATE MIGRATION COUNCIL

2. The Definitions

Migrants

An umbrella term, not defined in international law, reflecting the common understanding of a person who moves away from their place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons.4

Disaster

A “serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability, and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts.”5

Climate Mobility

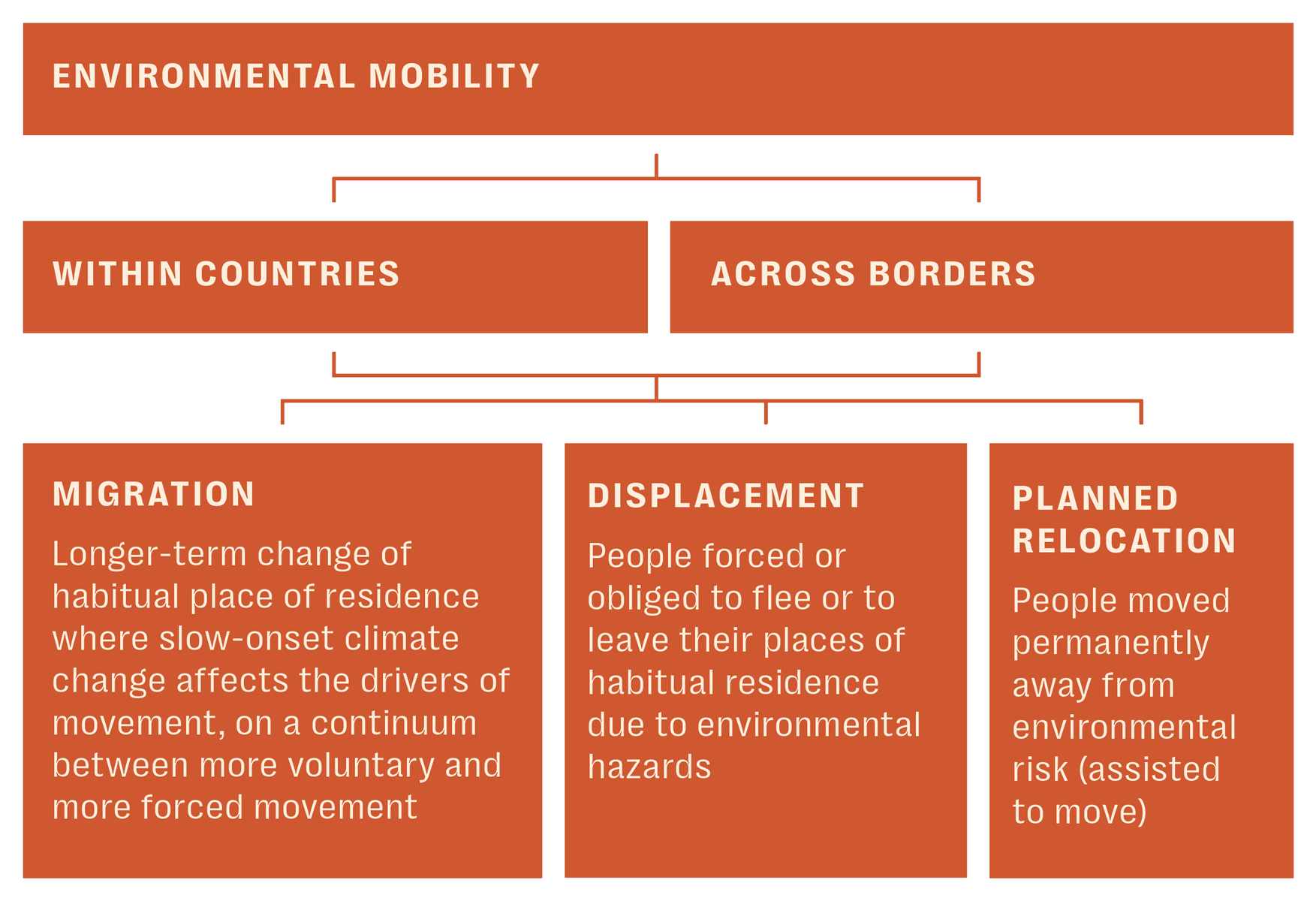

Understood to encompass three types of movement: (1) displacement, (2) migration, and (3) planned relocation. Most experts use displacement to refer to movement that is primarily forced; migration to refer to movement that is primarily voluntary; and planned relocation to refer to the planned movement of communities, typically within the same country.6 A fourth category refers to (4) trapped or immobile populations that are unable or unwilling to move despite severe climate hazards.

1. Disaster Displacement

The movement of persons who have been forced or obliged to leave their homes or places of habitual residence as a result of a disaster or in order to avoid the impact of an immediate and foreseeable natural hazard.7

2. Climate Migration

The movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a country or across an international border.8 Climate change is often categorized as a threat multiplier, that is, a factor that accelerates other factors that motivate the temporary or permanent movement of people from their communities of origin.

3. Planned Relocation

In the context of disasters or environmental degradation, including the effects of climate change, a planned process in which persons or groups of persons move or are assisted to move away from their homes or place of temporary residence, are settled in a new location, and provided with the conditions for rebuilding their lives.9

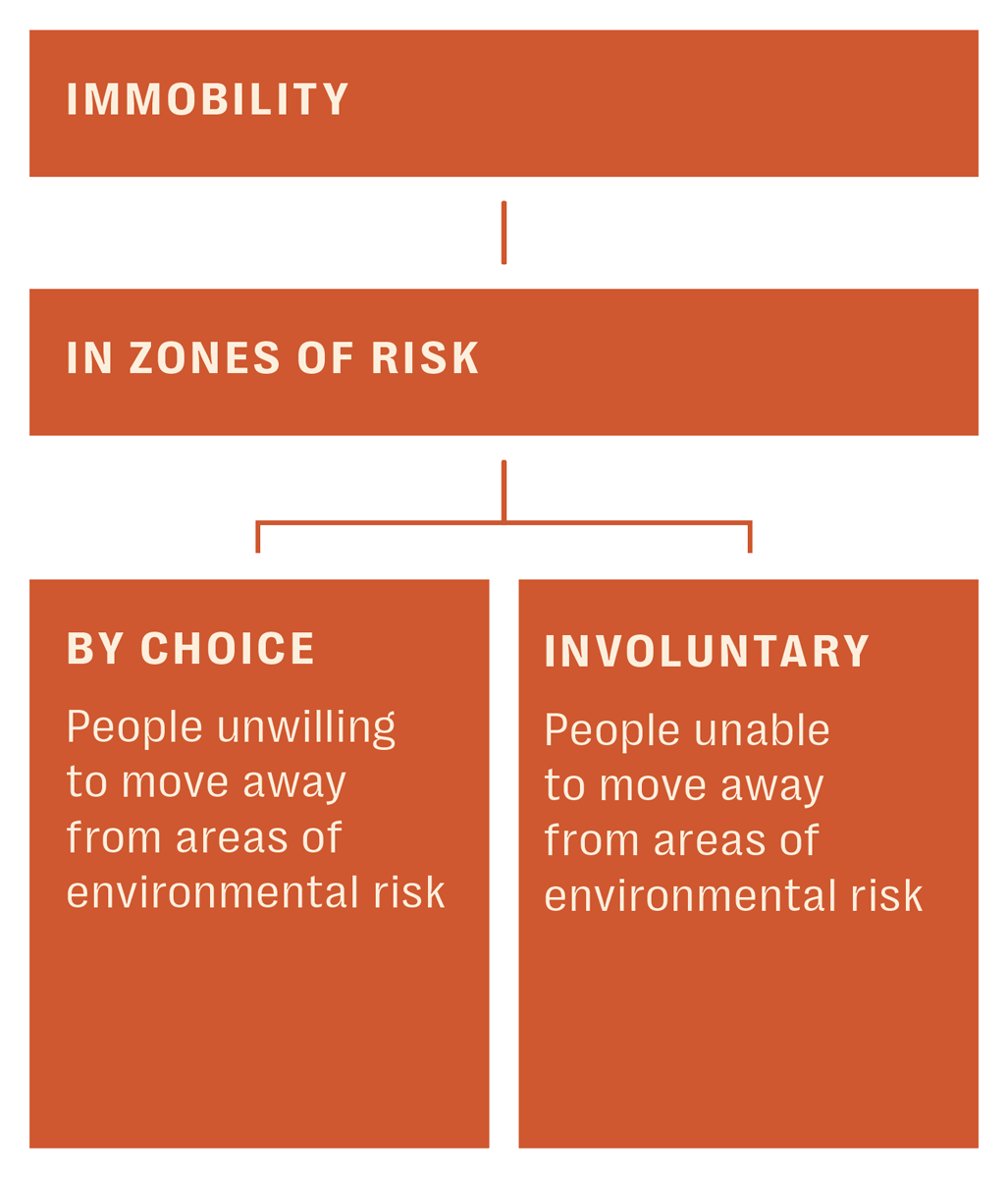

4. Trapped or Immobile Populations

“[P]opulations who do not migrate, yet are situated in areas under threat, [...] at risk of becoming ‘trapped’ [or having to stay behind], where they will be more vulnerable to environmental shocks and impoverishment.” This framing may apply to poorer households that may not have the resources to move and whose livelihoods are affected by environmental change.10 Alternatively, it may also apply to communities who do not desire to leave ancestral lands despite the challenges posed by climate change.

3. The Numbers

Quantifying the impacts of climate change on human movement is a difficult task. It is technically challenging to define and measure numbers of migrants and to isolate climatic drivers, given the multi-causal nature of most migration. Not all people affected by climate change have the capacity, opportunity, or willingness to move. Climate impacts may displace some populations multiple times from the same location.

Future projections must also be handled with extreme care, given the possibility that figures will be misinterpreted or misapplied and that multiple forces affect the interface between climate change and human mobility. That said, a variety of models and figures can present an idea of the challenges ahead:

Disaster-Related Internal Displacement:

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre,12 an average of 26 million new displacements have been recorded annually from 2018 to 2022 due to the impact of various disasters. In 2022 alone, 32.6 million new disaster displacements were registered worldwide, notably due to floods (59%) and storms (31%).

Internal Climate Migration:

The World Bank’s 2021 Groundswell Report signaled that without adequate climate action and development support, by 2050 climate change could lead more than 216 million people to become internal migrants in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and East Asia, and the Pacific.13

Cross-border Migration:

Adverse environmental factors tend to have stronger effects on internal, especially rural- urban, migration, than on cross-border migration. The data on cross-border disaster displacement flows remains limited, though some smaller-scale case studies exist exploring this facet of human mobility. These have produced a range of results that are not always consistent with one another.14

Exposure to Coastal Hazards:

Currently, 110 million people live in low-elevation coastal zones, but this figure could rise to 1 billion by 2050.15 This approximately tenfold expansion of coastal populations that are vulnerable to coastal erosion in just 20 to 30 years suggests how fraught it is to project the complex migration implications and dynamics that will result from destabilizing climate factors.

Where Humans Can Live:

The area of the human climate niche, understood as the part of the globe that is most suited for human life, will decrease drastically under severe climate change scenarios. In 2023, climate change has already put approximately one-tenth of the global population outside of this niche. By 2100, current emission scenarios and a global warming of 2.7°C would raise the number of people outside of the human niche to one-third of the global population.16

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CLIMATE MIGRATION COUNCIL

4. Guiding Principles

for Solutions

Given the powerful implications of climate change on human mobility, policymakers and leaders must deepen their understanding of the complexities of the relationship. In order to address existing and evolving challenges at that nexus, the suite of proposed solutions must account for local, national, and global dynamics.

They must account for and invite the full participation of the most affected—and typically least culpable—communities when developing responses. There will be no one-size-fits-all solution to these challenges given dramatically different local contexts and fluid geopolitical complexities. An array of interventions will be necessary to target the various dimensions of this nexus. Without proposing specific solutions, we offer a number of guiding principles that policymakers should consider:

Whenever possible, prevent or limit displacement associated with climate hazards.

The first principle, one conjoined with the goal of aggressively mitigating the worst climate impacts, is to enable people to remain in their homes when they desire to do so, thus diminishing the scale of forced migration. People displaced and uprooted by the climate emergency may lose access to their livelihoods, face human rights violations, and see their vulnerabilities increase. Supporting people’s capacity to remain in place—as an alternative to migration—when climate change dramatically alters their homes requires mitigating climate change through fast and drastic emissions reduction in line with the Paris Agreement. It also requires supporting locally-driven resilience and adaptation strategies to cope with worsening climate hazards, addressing loss and damage and the inequitable burdens facing vulnerable communities, and enhancing the availability of climate finance for those on the frontlines of the climate crisis.

Enable safe, regular, and orderly migration pathways that promote human dignity and climate justice.

While many people prefer not to move, the impacts of climate change on other socioeconomic forces make that choice hard or impossible for many others. For people who see no option but to leave their homes, policymakers must ensure the availability of safe and orderly internal and international migration pathways that provide options against climate impacts. Certain forms of mobility—such as evacuations, planned relocation, and labor migration—can make positive contributions to reducing exposure and vulnerability. Yet they can also present challenges when not well designed. Efforts must be deployed to establish functional and adequate frameworks to leverage the positive impacts of mobility on migrants and sending and receiving communities and to prevent harm.

Protect the rights of affected communities and people on the move.

All people, independent of their mobility status, are entitled to fundamental human rights in the climate emergency. The ways in which climate change affects the rights of exposed communities—including the rights to a healthy environment, decent housing, water, and life— require corrective action from responsible parties. At the same time, when people leave their homes, whether forced or not, they may become even more exposed to climate risks and human rights violations. These situations can affect people differently according to gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, economic status, indigeneity, and other characteristics, putting groups that are already structurally disadvantaged at higher risk. Internally displaced persons, internal migrants, and people moving across borders in contexts of disasters must have access to humanitarian assistance, protection, and development support that allows for the full realization of their human rights.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CLIMATE MIGRATION COUNCIL

5. Current Legal and

Policy Frameworks

It is abundantly clear that climate change plays an ever-increasing role in accelerating internal displacement and cross-border movement. Some legal and policy mechanisms are available to safeguard the rights of people on the move in this context, but they are not yet sufficiently reflected in either international law or within most domestic migration policies.

International

While there is no specific binding international convention addressing human mobility in the context of climate change, a number of areas of law already contain relevant principles, starting with human rights law, which applies to all people regardless of their situation and migratory status.

Internal disaster displacement is addressed in the 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacements. The role of disaster risk reduction is further detailed in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015– 2030). In the intersection between disaster risk reduction and migration policies, the 2015 Protection Agenda of the Nansen Initiative provides a non-binding blueprint to enhance protection for people displaced across borders in the context of climate change and disasters.

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, adopted in 2018, also makes specific recommendations aimed at ensuring safe human mobility in contexts of disasters, environmental degradation, and the adverse impacts of climate change.

In addition to the above frameworks focused on human rights and human mobility, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) also addresses human mobility in the context of climate change. In particular, the 2018 recommendations of the Task Force on Displacement seek to prevent displacement and to address the needs of populations on the move.

The humanitarian system is an important framework to guide responses for persons affected by disasters, notably in terms of humanitarian assistance and camp coordination and camp management, among other sectors.

National

In the national context, some countries have sought to address human mobility driven by climate change within their laws and policies.

Some state efforts have included increasing opportunities for temporary protection in the wake of climate disasters, broadening parameters for labor migration, or applying existing refugee law—which does not explicitly recognize a right to protection on account of climate displacement—in relevant circumstances. Other countries’ efforts include facilitating the planned relocation of populations in high-risk areas, leveraging the positive contributions of migrants and the diaspora, or integrating human mobility in climate change adaptation plans, among others.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CLIMATE MIGRATION COUNCIL

Learn more about the effects of climate change on human mobility: